1.25.15 with Shelby David Meier

This week the teens were introduced to Shelby David Meier, the artist who will lead the program for the next four classes. Shelby is a recent graduate of TCU and currently based in Fort Worth. He started the class with an introduction to his life and work. He is a conceptual sculptor and was a collaborator in the Fort Worth–based artist collective Homecoming Committee.

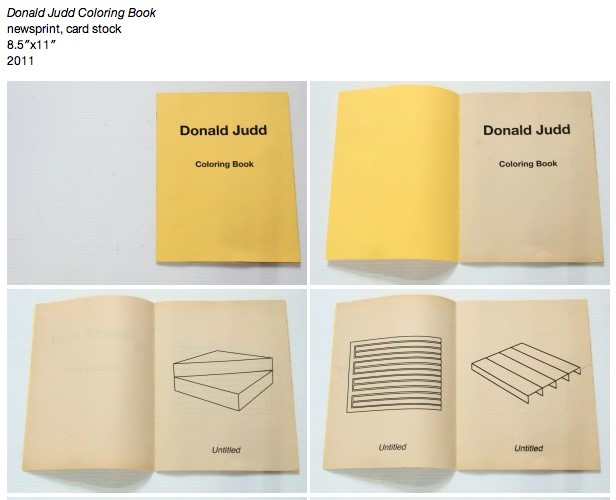

Shelby shared images and insight into his last few of years of work. The class quickly learned that he jumps around in his artistic process. He does not feel tied to one particular medium or mode of working, and he freely explores different processes and materials. Shelby explained that, though his works all look very different, there are similarities in the concepts in his output. Those concepts are incredibly important to the art that he makes. Shelby’s intelligent work has insightful references to film, literature, and other works of art (for example, see his Donald Judd Coloring Book below).

After Shelby answered a few questions, the class headed into the galleries to look at a few works in the Modern’s permanent collection. We started at Donald Judd’s Untitled from 1967.

Shelby led a conversation about Judd, Minimalism, and the notion of the “specific object.” He emphasized Untitled’s machine aesthetic and how there is no evidence of the artist’s hand or touch. He stressed that the concept of the work is incredibly important and how an artist can hand off plans to skilled craftsmen to fabricate the work.

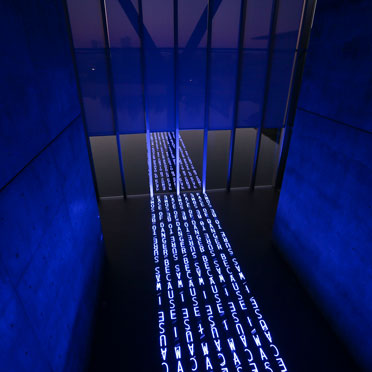

That made a perfect segue to the work of Sol LeWitt. The class explored his Wall Drawing #50A of 1970 and spoke in detail about the visual qualities of the work. Shelby explained the notion of Conceptual Art and elucidated on LeWitt’s process. As Judd had created plans for Untitled that were executed by others, LeWitt wrote instructions for his wall drawings that were then carried out by assistants. LeWitt created over a thousand works of conceptual art in his lifetime.

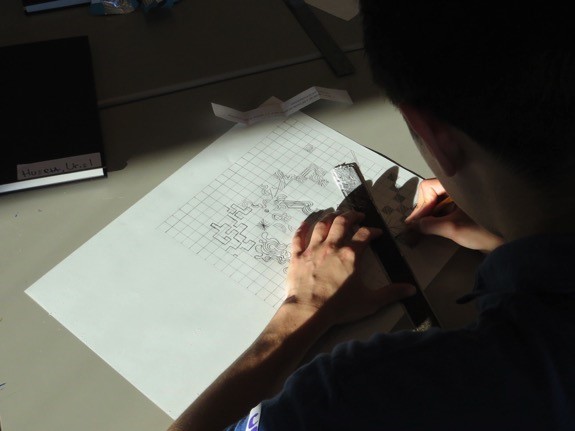

The class returned to the lecture room and watched a few videos on LeWitt’s works. Several videos had lengthy interviews with LeWitt’s studio assistants, who explained the extent of their involvement in each piece. The assistants refer to the set of instructions written by LeWitt, but each installation is inevitably distinct due to different interpretations of those instructions and different sites and situations. Shelby was interested in the notion of working from a predetermined set of instructions, so we headed back to the studio and prepared for our activity.

Shelby passed a bowl of balled-up pieces of paper and asked each student to take one. Each scrap had one of the following instructions on it:

- Draw a 20” x 20” square. Divide the square into four 10” x 10” sections. In one section, draw one line 1” long. In the second section, draw ten lines 1” long. In the third section, draw 100 lines 1” long. In the fourth section, draw 1000 lines 1” long.

- Draw a 20” x 20” square. Divide the square into 1” x 1” sections. In each section, draw between one and twenty freehand lines.

- Draw a 20” x 20” square. Divide the square into 1” x 1” sections. In each section, draw a diagonal line.

- Draw a 20” x 20” square. Divide the square into 2” x 2” sections. Within each square, draw not straight lines in any of four directions. Use only one direction in each square, but draw as many lines as desired. Draw at least one line in each square.

The results were intriguing. In even the most rigid assignments, students’ interpretations of the guidelines were vastly different. We ended the day with some homework; Shelby asked each student to create a list of instructions as a work of conceptual art to be given to another classmate to execute. We look forward to the results!